Feature Story

“STOP THE SPINNING WORLD”

BY BILL RUEHLMANN

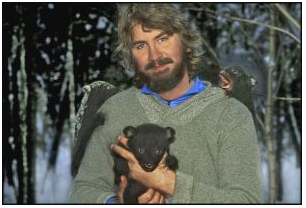

The portrait shows National Geographic photographer Raymond Gehman amid the snows of Maine holding two black bear cubs.

Gehman, grinning, is big and bearded, his large arms wrapped around the clinging cubs like hawsers.

Make that three bears.

But where is Mom?

“Sleeping,” drawls Gehman

He had been shooting the work of biologists who track and unearth hibernating bears who are quickly sedated to exchange signal-sending collars around their necks. Gehman had been handed the cubs for safekeeping. They stuck to him like Velcro.

So, in an uncharacteristic moment, somebody turned the camera on him, capturing more than a little of Gehman’s intrepid essence. Because he is a conservator, too, there is a protective passion in his pursuit of nature. The cubs are secure in Gehman’s embrace.

For the moment.

Gehman, 48, is an ecologist of the microsecond.

“It’s moments like these,” he confides, “that allow me to make sense of an often chaotic, confusing world. By composing the elements, choosing lenses, fiddling with a few gadgets and waiting for the precise light for the finishing touch, I preserve it on film. I have slowed down the spinning world, if only for a moment.”

Gehman was at Virginia Wesleyan College last Thursday to lecture on his work. He has ties here. Gehman’s niece and nephew, Melissa and Chris Harris, are students at the college. And for eight years, from 1982 to 1990, he was a staff photographer for The Virginian-Pilot.

While he was there, Gehman was named Virginia Newspaper Photographer of the Year for 1984 and 1985. He was Southern Newspaper Photographer of the Year for those same two years. And he was runner up as national Newspaper Photographer of the Year in 1984.

He entered and won a lot contests in those days. Gehman had an agenda.

He wanted to work for National Geographic magazine.

The contest victories were supposed to get the attention of the National Geographic Society.

They did.

Gehman made forts in the woods as a kid growing up in Fairvax, Va. He watched those woods get cut down for apartment houses. That dismaying spectacle may have been the genesis for his sense of the precious perishability of the natural world.

In the fourth grade he saw a slide show by a National Geographic photographer. “I was mesmerized,” he says. “Not just by the images but also by the idea that the guy’s job was outside – and in strange and faraway places.”

He bought his first camera after being drafted into the army in 1971.

After three years of service in Germany, he went to art school at Northern Virginia Community College where he was exposed to and inspired by the work of Robert Frank and Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Farm Security Administration documentation of the Depression. He studied journalism at the University of Missouri and went to work first for The Missoulian of Missoula, Mont., and then The Virginian-Pilot.

When Gehman was given a National Geographic assignment to shoot a book on “Yellowstone Country” in 1989, he knew his calling was shooting the natural world.

This he has done, covering stories from the ecology of fire to the disappearing wetlands to the vanishing prairie dog. He’s trekked Wyoming’s Bighorn Country, the Sanibel Island Gulf Coast of Florida, the Canadian Rockies and the rain forests of Belize. He’s shot grizzly bears and the aftermath of hurricanes, hot pools that can boil a drifting duck and nocturnal Apache ceremonial dancers.

His work is a kaleidoscope of wonder at the edge of the world.

Gehman is a great shambling guy, a 200-pounds-plus 6-footer who wears a tie this day to speak in, but you can tell his heart isn’t in appearances. He also wears the jeans and waterproof walking shoes of his working life. He looks like a 21st century version of trapper Jim Bridger, garbed in brand-name flannel and denim.

“I brought a tray of 80 slides,” Gehman told a rapt audience in a Wesleyan conference room, “which represents the best of 20 years’ work up to about last spring. But I’ve had a pretty good year. So I might have a few more.”

The year, a long way from over, includes three weeks in China and a four-day freelance shoot in Louisiana for Ford trucks that in itself brought enough money for a 12-month living wage. He has just finished shooting a project on “The Rockies from Yellowstone to Yukon” that is fraught with flat-out, jaw-drop, heart-stop imagery.

“That’s where I love to be,” says Gehman. “Where it’s wide-open and pristine. A sky with patchy clouds will give these beams of light, and you get to the top of the mountain and just hang out for a couple hours.”

So easy.

Gehman does huge research before a shoot. “Every time you get a new assignment, it’s like going back to school,” he says. “You don’t just get there and float around like a butterfly. You try to make a point.”

Then there’s the getting there. Hiring outfitters and wranglers and guides to get in and out alive. Riding horseback for 12 hours at a stretch.

You have to be in condition.

“I learned my lesson going up a glacier in Iceland,” says Gehman, who now trains rigorously before his trip. “Halfway up, I was done. I was dead.”

“The guide said, ‘I told you to get in shape!’ But I made it. It keeps me young.”

He has to learn to use climbing crampons and “ice picks and stuff” on the fly. Those things will shred a pair of waterproof pants in a heartbeat. Bugs, snakes, heat – solitude.

At times, a man – or a bear – can get grumpy out there.

But most of it is beauty.

The small stuff: an aspen leaf caught on a hat brim in the woods; bleached fishbone in a parched and cracked riverbed; a cowpoke’s boots hung drying over a wood stove in a camp tent.

The big stuff: an alpine meadow in Banff; the curl of the Snake River in Grand Teton Park; steam-wrapped bison at Yellowstone.

“You’re always looking for the moment,” Gehman say. “You want it to pop right off the page.”

Critters and wild places are his beat:

“When you’re on assignment, everything seems to be a picture. You never turn it off; you work seven days a week, dawn to dusk. You get totally involved.”

“It’s intense.”

He’s busiest at sunrise and sunset, when the light’s low on the horizon, and has more warmth of tone, and the shadows stretch like spreading fingers over the earth. “The main characteristic of a good photograph is that it triggers some sort of emotional response,” says Gehman. “It turns you on or turns you off. It reacts in your heart, or maybe your gut.”

Like a solitary buffalo caught crossing a two-lane blacktop, valuable, vulnerable and endangered as the Fairfax forest of his youth.

© 2021 Raymond Gehman. All rights reserved.

No content may be used whole, in part, individually, or as part of a derivative work without express permission from Raymond Gehman.